Why the Academic Library is your Friend as an Institutional Researcher

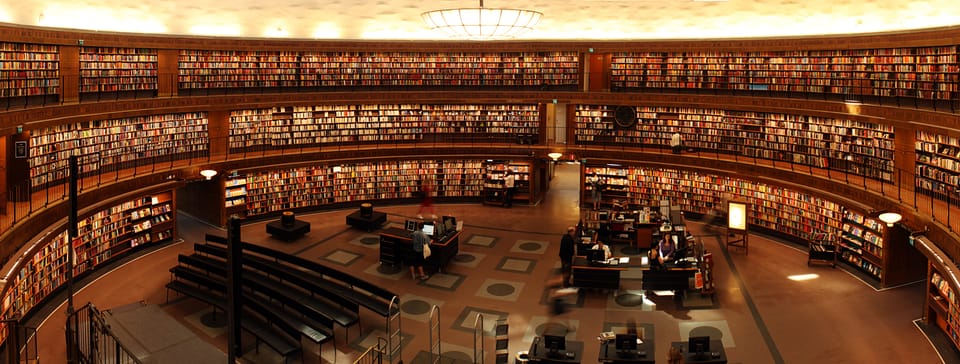

I’ve been working with student data, surveys, and reporting supporting enrolment management and decision making for nearly ten years. I started my institutional research (IR) career in an office with one other analyst, reporting to the Registrar. At the time, conversations about strategic enrolment management were rare in this small institution. I learned about SEM by attending conference presentations from large universities, and my colleague and I would come home dreaming of what we could build with a little more research time. As we matured our tool use, we found small efficiencies in our work. Initially, we used these small pockets of time for reading. I often visited the academic library on campus and collected articles talking about our big ideas.

I found resources like New Directions for Institutional Research, Research in Higher Education, and Journal of Assessment and Institutional Effectiveness and would save articles with the hope of eventually using them in my work. While conferences offered annual idea generation and excitement within the institutional research office, reading throughout the year kept me energized and interested in the work. It changed my focus from simply meeting the reporting expectations to creating research and exceeding expectations for what IR could produce. Giving analysts time to read, research, and collect ideas is a simple analyst retention strategy. Analysts' work can be mundane and repetitive, but keeping up with the current conversations and literature can help analysts dream beyond the slog of data validation and government reporting, to having a sense of their work more directly affecting students.

I was lucky to come to IR with a library background. I grew up as a “library kid”, attended programs, volunteered, and would come home weekly with a stack of books. After my degree, I went back to school to study library and information technology. This gave me the skills that prepared me for IR, and a learning-oriented career perspective which influenced the new vision for the office. As the profile of our office grew, we began to have individuals from other offices come to us for unofficial conversations about research approaches and data use. On my lunch breaks, I’d talk with colleagues working on their graduate studies, or those recently promoted to manager positions, and answer questions about research approaches and sources. My first suggestion is to talk to a librarian.

Academic libraries, even in institutions that are focused on two-year and undergrad studies, will have resources for staff professional development. An academic library serves not only students, but the administration and staff. Just as SEM seeks to unite an institution’s community together under a collective vision, libraries have long understood their role in supporting the needs of the entire community. Plus, Librarians are source-tracing experts. They can help you collect a robust reference and resource list, track the historical development of a theory or approach, and find relevant sources from non-higher education publications to provide additional context and nuance to a project. When a resource is not in the catalogue, librarians can request the item through an inter-library loan. Academic libraries have resource sharing agreements so they can share expensive texts that might be used once or twice without having to purchase them. The library only incurs the cost of shipping the item, and you still get the information.

Libraries provide access to a range of sources and formats. Academic library collections include a robust set of online research databases, ebooks, microfiche, print journals, government publications, and may act as an institution’s internal document archive. Research databases are constantly updated with new articles and journals, enabling analysts to keep up with trends and conversations in higher education across the sector throughout the year. The breadth and depth of sources enable analysts to better develop, expand, and adapt a project to meet the unique needs of their institution. Using peer-reviewed sources can increase the quality of analysis and expand data use by an institutional research office.

Sources

Journal articles range from statistical models and managerial approaches for growing the institutional research office to developing data governance and supporting SEM. The range of topics, number of resources, and potential use cases is as broad as a person could imagine. Reviews of software products found in sector-oriented journals can also inform the writing of a business case or purchase proposal.

Dissertations can be a key source for research about unique institutions, cultures, and regional settings. Someone has likely already attempted and evaluated various models at an institution similar to yours. These dissertations, while not considered peer-reviewed sources, can highlight key challenges and themes to expect when developing and implementing a new project. Often, they include a discussion about feedback from end-users, which can help an analyst prepare for onboarding administration and suggesting some change management techniques.

Institutional archives may hold previous research projects, survey questionnaires, and environmental scans, which provide historical context for new analysts. They may also answer questions about how previous research questions were handled, and what led to the eventual discontinuation of a project. This can be key to making informed decisions about process and approach in the early stage of a new project.

Books are also a key resource for institutional researchers, especially in SEM institutions. As SEM functions best under a collaborative effort, research analysts are often highly skilled at taking in and summarizing complex information. Given time to read or skim a book on a topic related to a developing strategy of a SEM committee or task force, the analyst often can translate these theoretical concepts into actual practices. With this information, analysts can become key advocates for implementing a strategy, to identifying challenges for implementing it within an institution’s information system, and understanding the additional workload this might put on their work and the work of other committee members. Reading beyond just their own work also gives analysts exposure to the language and concerns of academics and administration, which helps an analyst have better planning and discovery conversations, write better reports, presentations and design training for these groups.

Mutual benefit

When library purchases are added to the library’s reference or lending collection, it’s likely the cost will come out of the library’s purchasing budget. Purchasing resources this way can ensure Institutional Research’s budget remains untouched for other professional or office development opportunities. Adding items to the collection also ensures accessibility not only for your office but for committee and task force members, staff looking for more responsibility or who might be preparing to step into a new role, and for new directors or managers looking to understand how to interpret and use data to make decisions.

Library staff get excited about research on campus. By establishing this relationship, you might be lucky enough to receive an email from a librarian when a new related resource comes in, or when they see a journal come in with an article list that they think might interest you. If they get to know you as a good question-asker, and connect your work with the student experience, library staff can become early SEM adopters, promote IR reports to staff and students, and may even reach out to discuss opportunities to collaborate on data-blending their circulation data with student data for mutually beneficial research projects.

Like analysts, library staff are also data oriented. Librarians collect stats on all kinds of resource use, number of contact points, complexity of questions, and time spent helping patrons with research. These stats inform staffing levels, scheduling, and budgets; employee use of the library supports their continued operation.

Upfront research and ongoing reading can help institutional research staff identify opportunities for new research, develop better analysis, make sound software purchases, and understand the pros and cons of different statistical approaches to various modelling projects.

Not only are libraries a place of research and knowledge for students, but they should be seen as the same for internal research staff and planners. Just like institutional research analysts get excited about good questions, so do librarians. And most library staff won’t hesitate to tell you that an analyst’s research questions are always more interesting than whatever cataloguing task they’re working on.

Want to grow your institutional research analytics, but not sure where to start?